Reversing Serato's GEOB tags

Fri 12 July 2019The popular DJ application Serato DJ Pro stores a lot data in GEOB-type ID3 tags of MP3 files. This way, users can share beatgrids, hot cue points, saved loops and more by just copying over an MP3 file.

Unfortunately, the format is not publicly documented. Thus, I figured it could be fun to try to learn how these formats work the hard way(tm).

Setup and Preparation

As example file I used Perséphone - Retro Funky (SUNDANCE remix), which is licensed under the term of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) license.

$ lame -b 320 Perséphone\ -\ Retro\ Funky\ \(SUNDANCE\ remix\).wav

LAME 3.100 64bits (http://lame.sf.net)

Using polyphase lowpass filter, transition band: 20094 Hz - 20627 Hz

Encoding Perséphone - Retro Funky (SUNDANCE remix).wav

to Perséphone - Retro Funky (SUNDANCE remix).mp3

Encoding as 44.1 kHz j-stereo MPEG-1 Layer III (4.4x) 320 kbps qval=3

Frame | CPU time/estim | REAL time/estim | play/CPU | ETA

8170/8170 (100%)| 0:03/ 0:03| 0:03/ 0:03| 68.457x| 0:00

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

kbps LR MS % long switch short %

320.0 99.1 0.9 87.8 6.3 5.8

Writing LAME Tag...done

ReplayGain: -10.6dB

Initially, there are no tags in the resulting MP3 file:

$ eyeD3 -v original.mp3

.../original.mp3 [ 8.14 MB ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Time: 03:33 MPEG1, Layer III [ 320 kb/s @ 44100 Hz - Joint stereo ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No ID3 v1.x/v2.x tag found!

Next, I'm starting up a Windows 10 VM with Serato DJ Pro 2.1.1 installed. For some reason Serato causes my CPU usage to go up to 100%, but that can be ignored since we're not doing anything latency-critical.

To make testing easier, I'll just put the MP3 file into a separate directory on my host system and create a Samba network share to access it from inside the VM. Serato does not list network shares in the sidebar, but it's still possible to load tracks from network shares into a deck directly by using drag and drop from a file explorer window.

First, let's just load the tack into deck 1, wait until Serato is done with analyzing it and then ejecting it to make sure that ID3 tag changes are written to the file.

We can see that the file has indeed changed by comparing it to the original file:

$ sha1sum original.mp3 analyzed.mp3

521974eb217ef001e6df426d1e2908cd80c39b6b original.mp3

46e7f16f735758b4d85730b639c908850860537b analyzed.mp3

$ eyeD3 -v analyzed.mp3

eyed3.id3.frames:WARNING: Frame 'RVAD' is not yet supported, using raw Frame to parse

.../analyzed.mp3 [ 8.16 MB ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Time: 03:33 MPEG1, Layer III [ 320 kb/s @ 44100 Hz - Joint stereo ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ID3 v2.3:

title: Perséphone - Retro Funky (SUNDANCE remix)

artist:

album:

album artist: None

track:

BPM: 115

GEOB: [Size: 3842 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Overview

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 2 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Analysis

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 22 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Autotags

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 318 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Markers_

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 470 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Markers2

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 15 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato BeatGrid

Filename:

GEOB: [Size: 16401 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Offsets_

Filename:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 ID3 Frames:

TIT2 (52 bytes)

TCON (11 bytes)

TKEY (13 bytes)

RVAD (20 bytes)

TBPM (14 bytes)

GEOB x 7 (21441 bytes)

512 bytes unused (padding)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The GEOB tags look interesting, so let's dump them to individual files for further analysis:

$ eyeD3 --write-objects analyzed analyzed.mp3

eyed3.id3.frames:WARNING: Frame 'RVAD' is not yet supported, using raw Frame to parse

.../analyzed.mp3 [ 8.16 MB ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Time: 03:33 MPEG1, Layer III [ 320 kb/s @ 44100 Hz - Joint stereo ]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ID3 v2.3:

title: Perséphone - Retro Funky (SUNDANCE remix)

artist:

album:

album artist: None

track:

BPM: 115

GEOB: [Size: 3842 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Overview

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Overview.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 2 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Analysis

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Analysis.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 22 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Autotags

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Autotags.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 318 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Markers_

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Markers_.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 470 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Markers2

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Markers2.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 15 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato BeatGrid

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato BeatGrid.octet-stream...

GEOB: [Size: 16401 bytes] [Type: application/octet-stream]

Description: Serato Offsets_

Filename:

Writing analyzed/Serato Offsets_.octet-stream...

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A first look

Now let's have a look at the tag data and see if we can determine the meaning of it.

The Serato Analysis tag only contains 2 bytes, so let's look at that one first.

$ hexdump -C analyzed/Serato\ Analysis.octet-stream

00000000 02 01 |..|

00000002

It's just a suspicion, but the numbers 02 01 look like the major/minor part of the version number of Serato that was used for analysis (2.1.1).

The hexdump of next larger tag (in terms of byte length), Serato BeatGrid, is inconclusive at the moment, but Serato Autotags contains recognizable data:

$ hexdump -C analyzed/Serato\ Autotags.octet-stream

00000000 01 01 31 31 35 2e 30 30 00 2d 33 2e 32 35 37 00 |..115.00.-3.257.|

00000010 30 2e 30 30 30 00 |0.000.|

00000016

We can easily see that the tag contains the string 115.00, which is also the BPM value that is displayed by Serato.

There are two more ASCII strings in there, but I'm not sure what they are for.

Next, let's have a look at hexdump of Serato Markers2:

$ hexdump -C analyzed/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream

00000000 01 01 41 51 46 44 54 30 78 50 55 67 41 41 41 41 |..AQFDT0xPUgAAAA|

00000010 41 45 41 50 2f 2f 2f 30 4a 51 54 55 78 50 51 30 |AEAP///0JQTUxPQ0|

00000020 73 41 41 41 41 41 41 51 41 41 00 00 00 00 00 00 |sAAAAAAQAA......|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

000001d0 00 00 00 00 00 00 |......|

000001d6

The ASCII data in that file certainly looks like it has been base64-encoded. Let's verify that that assumption and see what's inside:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' analyzed/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | hexdump -C

00000000 01 01 43 4f 4c 4f 52 00 00 00 00 04 00 ff ff ff |..COLOR.........|

00000010 42 50 4d 4c 4f 43 4b 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 |BPMLOCK.......|

0000001e

The Serato Overview tag is almost 4 KB in size. The ASCII representation that is generated by hexdump -C looks quite familiar:

This tag obviously contains the data for the track overview in Serato.

The remaining tags, Serato Markers_ and Serato Offsets_ contain a lot of repeating data, but it's uncertain what it means.

Looking for changes

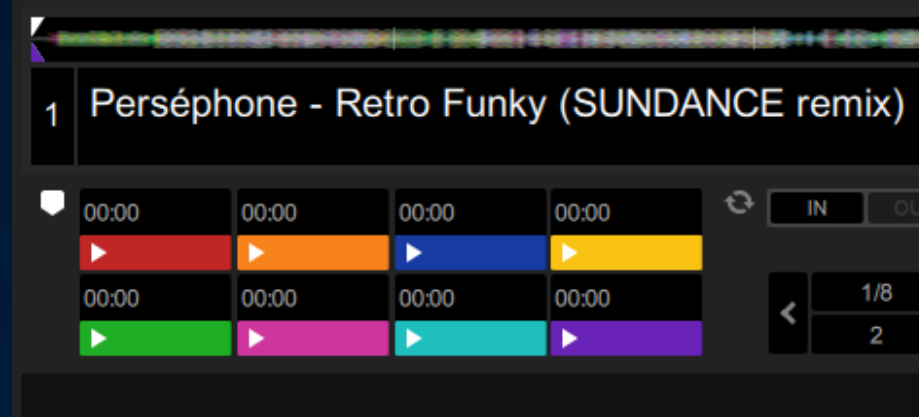

Now, let's take our analyzed file and set a hot cue point.

Again, we eject afterwards and use eyeD3 to write the data inside the ID3 GEOB tags to a directory:

$ mkdir hotcue-00m00s0-red

$ eyeD3 --write-objects hotcue-00m00s0-red hotcue-00m00s0-red.mp3

<output removed>

$ cd hotcue-00m00s0-red

Next, let's check if anything changed:

$ for file in *.octet-stream; do diff -q "$file" "../analyzed/$file"; done

Files Serato Markers2.octet-stream and ../analyzed/Serato Markers2.octet-stream differ

Files Serato Markers_.octet-stream and ../analyzed/Serato Markers_.octet-stream differ

Both Serato Markers_ and Serato Markers2 have been modified.

Let's look at Serato Markers2 first.

Before setting the cue point, that file just contained base64-encoded data and some zero bytes.

This is still the case, but the base64-encoded data has grown in size:

$ hexdump -C Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream

00000000 01 01 41 51 46 44 54 30 78 50 55 67 41 41 41 41 |..AQFDT0xPUgAAAA|

00000010 41 45 41 50 2f 2f 2f 30 4e 56 52 51 41 41 41 41 |AEAP///0NVRQAAAA|

00000020 41 4e 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 41 4d 77 41 41 41 |ANAAAAAAAAAMwAAA|

00000030 41 41 41 45 4a 51 54 55 78 50 51 30 73 41 41 41 |AAAEJQTUxPQ0sAAA|

00000040 41 41 41 51 41 41 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |AAAQAA..........|

00000050 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

000001d0 00 00 00 00 00 00 |......|

000001d6

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | hexdump -C

00000000 01 01 43 4f 4c 4f 52 00 00 00 00 04 00 ff ff ff |..COLOR.........|

00000010 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc |CUE.............|

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 42 50 4d 4c 4f 43 4b 00 00 00 00 |.....BPMLOCK....|

00000030 01 00 00 |...|

00000033

When we compare it with the previous content, we can see that these 21 bytes have been added:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | tail -c +17 | head -c -14 | hexdump -C

00000000 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc |CUE.............|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 |.....|

00000015

Except for the first 3 bytes that say CUE in ASCII, we don't really know what these values mean though.

To determine what the individual bytes mean, we can change something and check how these are represented in the ID3 tags. For example, when the cue color is changed to blue, the content of the base64-encoded data changes as well:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' hotcue-00m00s0-red/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | tail -c +17 | head -c -14 | hexdump -e '"%08.8_ax " 21/1 "%02X " "\n"'

00000000 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00 00 00

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' hotcue-00m00s0-bue/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | tail -c +17 | head -c -14 | hexdump -e '"%08.8_ax " 21/1 "%02X " "\n"'

00000000 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00

As we can see, the cc byte has moved two bytes to the right, i.e. cc 00 00 became 00 00 cc.

If that 3-byte value is interpreted as RGB channel values, cc 00 00 is indeed red and 00 00 cc is blue.

Next, we compare it with a file that 8 cuepoints in different colors.

The data looks like this:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' hotcue-colors/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | tail -c +17 | head -c -14 | hexdump -e '"%08.8_ax " 21/1 "%02X " "\n"'

00000000 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00 00 00

00000015 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 cc 88 00 00 00 00

0000002a 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00

0000003f 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 cc cc 00 00 00 00

00000054 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00 00

00000069 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 05 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 cc 00 00 00

0000007e 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 06 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc cc 00 00 00

00000093 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 07 00 00 00 00 00 88 00 cc 00 00 00

As we would expect, there are 8 different entries with 8 different values at the position the color could be stored.

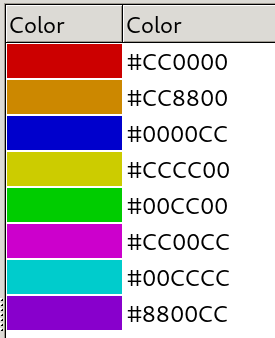

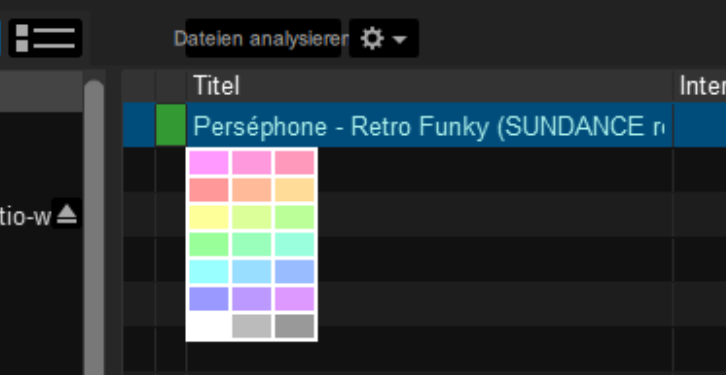

Using gpick, we check if the colors actually match:

Bingo! These colors look a lot like those displayed in Serato.

However, the colors displayed in Serato are slightly different.

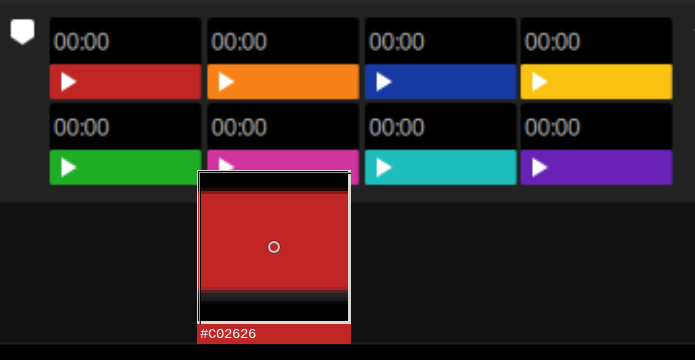

When using a color picker tool (e.g. gpick), we can see that the red displayed in the UI is in fact #c02626:

However, since the colors and their indices match so well, this can't really be coincidence. It suppose there's some kind of color scheme or transformation applied to these values.

Diving deeper into the Serato Markers2 internals

Since color information seem to be easily recognizable, we can use this to check if tracklist colors are stored in the Serato Markers2 tag as well.

Hence, let's the tracklist color to green:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' tracklist-color/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | hexdump -C

00000000 01 01 43 4f 4c 4f 52 00 00 00 00 04 00 99 ff 99 |..COLOR.........|

00000010 42 50 4d 4c 4f 43 4b 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 |BPMLOCK.......|

0000001e

Since the color #99FF99 is green, the bytes 99 ff 99 seem to be RGB channel values for the track color.

It makes sense to recapture our findings regarding the Serato Markers2 tag and see if we can see a pattern:

1. The base64-content starts with `01 01`...

2. ... followed by multiple entries, where:

1. Each entry starts with a zero-terminated ASCII string denoting the entry type.

2. `COLOR` entries contain 8 more bytes.

3. `CUE` entries contain 17 more bytes.

4. `BPMLOCK` entries contain 6 more bytes.

How would Serato parse this data? Each entry has a different size, even when we leave out the zero-terminated entry type. While it might be possible that Serato has a built-in mapping of entry types and their lengths, this would make it impossible to add new entry types in a backward-compatible way. Older versions would have no way to determine the length and thus can't skip the entry because they do not know where the next entry starts.

Let's look closer at the first few bytes of each entry:

1. `COLOR` entries contain 8 bytes and start with `00 00 00 04`.

2. `CUE` entries contain 17 bytes and start with `00 00 00 0d`.

3. `BPMLOCK` entries contain 6 bytes and start with `00 00 00 01`.

If we parse the first 4 bytes as 32-bit integer (little-endian), we can reasonably assume that determine the entry's length (excluding the integer itself).

But wait, this doesn't work for BPMLOCK entries since they contain 2 more bytes, even though according to the length value there should only be 1 byte.

Does this mean that our assumption is wrong?

No, not necessarily:

Since BPMLOCK is the last entry inside the base64-encoded data, it's possible that the last byte (00) doesn't actually belong to the BPMLOCK entry.

Instead it could be a sentinel value to tell Serato to stop parsing entries.

Hotcue positions

Now it's time to decode the hotcue positions. To achieve this, I created a 5 hotcues with (hopefully) recognizable positions:

| Hotcue | Position | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 00:00.0 |

Start of the file |

| 2 | 03:38.4 |

End of the file |

| 3 | 01:00.0 |

|

| 4 | 00:00.1 |

|

| 5 | 00:01.0 |

Looking at the hexdump, it is apparent that the 5 bytes between the hotcue index and the color contains the position:

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' hotcue-positions-00m00s0-03m38s4-01m00s0-00m00s1-00m01s0/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | tail -c +17 | head -c -14 | hexdump -e '"%08.8_ax " 21/1 "%02x " "\n"'

00000000 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00 00 00

00000015 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 01 00 03 55 58 00 cc 88 00 00 00 00

0000002a 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 02 00 00 ea 64 00 00 00 cc 00 00 00

0000003f 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 03 00 00 00 6c 00 cc cc 00 00 00 00

00000054 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 0d 00 04 00 00 03 f7 00 00 cc 00 00 00 00

It is likely that the position will be some kind of int or float value.

Since we already found little-endian values, the value will probably have little-endian byte order as well.

Since both types are only 4 bytes long, we do not know which bytes belongs to another field. However, we can easily check all possibilities and see if we recognize something:

$ python

Python 3.7.3 (default, Jun 24 2019, 04:54:02)

[GCC 9.1.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> data = [

... '00 00 00 00 00',

... '00 03 55 58 00',

... '00 00 ea 64 00',

... '00 00 00 6c 00',

... '00 00 03 f7 00',

... ]

>>> import binascii

>>> x = [binascii.unhexlify(x.replace(' ','')) for x in data]

>>> x

[b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00', b'\x00\x03UX\x00', b'\x00\x00\xead\x00', b'\x00\x00\x00l\x00', b'\x00\x00\x03\xf7\x00']

>>> bindata = [binascii.unhexlify(x.replace(' ','')) for x in data]

>>> import struct

>>> for x in bindata:

... print('%10d %10d %3.10e %3.10e' % (struct.unpack('>xI', x)[0], struct.unpack('>Ix', x)[0], struct.unpack('>xf', x)[0], struct.unpack('>fx', x)[0]))

...

0 0 0.0000000000e+00 0.0000000000e+00

55924736 218456 6.2696093227e-37 3.0612205732e-40

15361024 60004 2.1525379342e-38 8.4083513053e-41

27648 108 3.8743099942e-41 1.5134023415e-43

259840 1015 3.6411339297e-40 1.4223179413e-42

Now let's look at the results while keeping in mind that: - Hotcue 2 has been placed at 03:38.4 = 218.4 seconds = 218400 milliseconds - Hotcue 3 has been placed at 1 minute = 60 seconds = 60000 milliseconds. - Hotcue 4 has been placed at 0.1 seconds = 100 milliseconds. - Hotcue 5 has been placed at 1 second = 1000 milliseconds.

Column 2 is obviously containing the values we're looking for. This means that the 4 bytes following the hotcue index value contain the position in milliseconds as little-endian integer.

What's your name?

Since it's also possible to assign textual names to hot cue points in Serato, let's check how these are stored.

After preparing a file with 3 named hotcues and dumping its tags, a quick glance at hexdump's output confirms that the names are also stored in Serato Markers2.

$ grep -Poaz '[\w/]*' hotcues-with-names/Serato\ Markers2.octet-stream | tr -d '\0' | base64 -d | hexdump -C

00000000 01 01 43 4f 4c 4f 52 00 00 00 00 04 00 ff ff ff |..COLOR.........|

00000010 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 1a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 cc |CUE.............|

00000020 00 00 00 00 48 65 6c 6c 6f 2c 20 57 6f 72 6c 64 |....Hello, World|

00000030 21 00 43 55 45 00 00 00 00 15 00 01 00 03 55 58 |!.CUE.........UX|

00000040 00 cc 88 00 00 00 c3 a4 c3 b6 c3 bc c3 9f 00 43 |...............C|

00000050 55 45 00 00 00 00 13 00 02 00 00 ea 64 00 00 00 |UE..........d...|

00000060 cc 00 00 c3 a9 c3 a8 c3 aa 00 42 50 4d 4c 4f 43 |..........BPMLOC|

00000070 4b 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 |K.......|

00000078

As we can see in hexdump's ASCII output, the first hotcue is named Hello, World!.

To check how non-ASCII chars in hotcue names are encoded, hotcue 2 and 3 were named äöüß and éèê.

My guess that UTF-8 has been used turned out to be correct.

Saved Loops

Using the same approach as above can be used to determine how saved loops are stored.

One problem popped up is that Serato may insert linefeed characters 0a into the base64 string.

Also, the base64 string may lead to decoding errors caused by an invalid length. In that case the last byte can apparently just be ignored.

What's left to do?

A lot. Some fields in the Serato Markers2 are still unmapped, and I didn't really look at the Serato Offsets_ and Serato_Markers_ tags.

Maybe some fields could be edited manually to see how Serato reacts to these changes?

I was mainly doing this to add support for importing Serato Hotcues to Mixxx, an excellent free and open-source DJ application that runs on Windows, Mac and Windows. Also, I didn't investigate how Serato Flips are stored since such a functionality is not implemented in Mixxx yet.

Data dumps, example scripts and further information can be found at my GitHub repository. If you want to help completing the documentation of Serato's GEOB data formats, feel free to send me a pull request.